(Aotea News, June 2011)

Dr Michael Crooke

Chemical pathologist

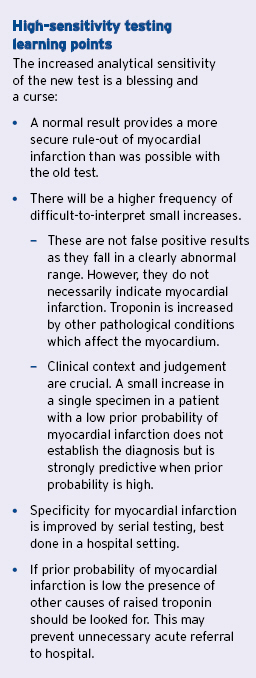

The high sensitivity test for troponin T, introduced last year at Wellington SCL, has significant benefits for the early recognition of patients with evolving acute myocardial infarction, especially in a hospital setting.

It does, though, present challenges in interpretation when used in primary care.

The best information is obtained from hs-TnT when serial testing is carried out during the first 12-24 hours after the clinical event that suggested an acute coronary syndrome, especially when clinical features and ECG are inconclusive. Changing values, with either a rising or falling pattern, are used as a determinant of myocardial infarction.

Serial testing is rarely done in primary care. Patients with a high probability of acute coronary syndrome on clinical grounds should be sent to hospital without waiting for even a single result of biochemical markers of cardiac ischaemia.

Use in rule-out of myocardial infarction

A traditional use of testing for troponins in primary care has been for rule-out of myocardial infarction in a stable patient with atypical or inconclusive symptoms and a low prior probability of MI.

Often the symptoms may have occurred more than 12 hours before presentation, have now resolved and ECG has been unhelpful.

The presence of a ‘normal’ result then provides a very low post-test probability of myocardial infarction, essentially a rule-out.

A raised result in these circumstances is much more difficult to interpret. It has been suggested that the high sensitivity test is not as good at rule-out of myocardial infarction as was the previous test for troponin T because the new test gives a high frequency of false positive results (nonspecific). This is incorrect: ruleout is related to sensitivity, not specificity.

The previous test did not provide very high probability of rule-out of myocardial infarction because it gave false negative results, but a normal result with the new test is a very secure rule-out.

The old test could not measure at the levels specified as important in the universal definition of myocardial infarction. This level is defined as that found at the 99th centile of a normal reference population. Thus, only one in a hundred healthy people will have a result above this and even then it will not be more than a few units higher.

The 99th centile for high-sensitivity troponin T is considered to be 13ng/L. By way of comparison, the old test was unable to measure reliably at levels below 0.03ug/ml, and this corresponds to a level somewhere between 40 and 50ng/L with the new test. (The conversion is not simply a matter of x1000 to convert ug/ml to ng/L.)

This means that elevations of three to four times above the 99th centile could not be detected with the old test. A result stated as <0.03 was not necessarily a rule-out of myocardial infarction but could have been a false negative.

The new test is so sensitive it measures reliably under the 99th centile, to levels of 4-5ng/L, giving greater security of rule-out.

Use in rule-in of myocardial infarction

It is true that results higher than the 99th centile will be seen more frequently in patients who do not have myocardial infarction than was observed with the old test.

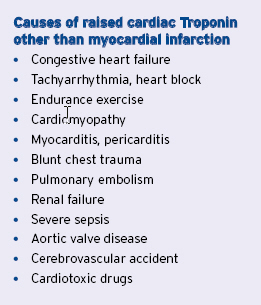

The clinical conundrum is that a single raised result neither rules in nor rules out myocardial infarction. The point is that raised Troponin is a marker of myocardial damage caused by many conditions, not just acute myocardial ischaemia. (Refer to table.)

Some of these elevations may be quite small but there is no specific level for a single result at which the result can be said to be definitely myocardial infarction or not.

Any elevation of troponin above the 99th centile should be considered to be abnormal but must be interpreted carefully in the clinical context in which it was ordered.

If the probability of myocardial infarction seems to be very low on clinical grounds then the possibility of a non-ischaemic cause should be investigated.

This was also the case with the old test but small elevations will be more apparent with the high sensitivity test. Some of these causes of raised troponin may themselves be grounds for acute referral.

The increased frequency of elevated results seen with the high-sensitivity test has lead to the development of algorithms to improve the specificity for diagnosis of myocardial infarction.

These algorithms are still in development but the one in use nationally for high-sensitivity troponin T requires an increase above the 99th centile and a serial result showing an increase of 50 per cent when the first result is less than 50ng/L, or an increase of 20 per cent when it is 50ng/L or more.

The detailed algorithm has been circulated previously, although it is expected to be used mainly in hospital practice.

Inappropriate use

A good rule is not to order troponin nless there has been some acute event which raises reasonable suspicion of myocardial ischaemia. Some people request troponin as part of what appears to be routine cardiovascular risk screening, with no clear reason nor with any strategy to interpret and use the results.

Current research shows that in completely asymptomatic people, especially older populations with increased cardiovascular risk, such screening will give a frequency of raised troponin in up to 5 per cent of cases.

However, none of these studies have defined any useful cut points nor have they provided information to guide therapy in primary prevention. This use of troponin should remain firmly in the research area. Current funding does not support the use of troponin in screening and Wellington SCL regards all requests as urgent.

Please provide contact details so we can contact you about abnormal results at any time, including out of hours.